Our Situation

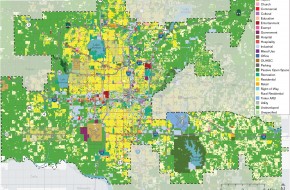

Citywide Development Patterns

In Oklahoma City (and most American cities), development tends to locate in single-use areas, surrounded by similar uses, densities, and buildings. There are at least four powerful reasons for this pattern.

First, developers tend to be specialists in certain project types, each with different practices and economics. For example, single-family home builders focus on doing what they do best, namely building single-family houses. Commercial developers concentrate on building and renting strip centers, and apartment builders build apartments, and generally do not venture out into less familiar waters.

Second, people tend to surround themselves with familiar environments. America is still largely a nation of homeowners, and a family’s home is usually its major capital asset. We protect that asset by avoiding uncertainty in the real estate market, instead surrounding ourselves with other homes of similar size and value. This also causes us to put more distance between ourselves and different types of development.

Third, contemporary development tends to increase the impact of some land uses on others. For example, as shopping centers, strip centers, and big-box stores became more prevalent, the impacts of traffic, large parking lots, lighting, service areas, and building size also increased. We like the ability to drive to these facilities, but don’t like the problems that grow from that convenience. This again causes us to demand greater separation between uses, in turn spreading them further apart and reducing street connections and walkability.

Fourth, land development ordinances encourage separation of uses. Ordinances responded to real and potential land use conflicts by separating different uses into “zones.” Each zone has a specific list of permitted uses, with limits on such factors as building height and density. Single-use zoning was a logical response to the demands of constituents. But it also produced a pattern of compartmentalized growth. In Oklahoma City, we have almost fifty different zoning districts, some of which are fashioned around the special characteristics of individual parts of the city like our cultural and historic districts. But, by and large, our ordinances make creative and desirable kinds of development difficult, lacking the flexibility to control potential conflicts in more creative ways.

These forces are strong, and they produce challenges for the city. These include:

- Lower-density, more dispersed urban development that strains the city’s operating budget and increases the cost per unit of public safety, water, waste disposal, and transportation services and infrastructure.

- Reduced walkability, affecting public health and fitness by making it more difficult for people to incorporate routine physical activity into their lives.

- More dependence on automobile transportation and increases in the distance of individual trips, affecting emissions levels and making it more difficult for the city to attain air quality standards.

Interestingly, planokc‘s Housing Demand and Community Appearance surveys indicated a preference for walkable communities that incorporated mixed uses. These preferences appear most pronounced among younger population groups, who display a strong appreciation for urban living. The popularity of districts like the Paseo, Midtown, Automobile Alley, and the Plaza District are expressions of these changing viewpoints.

Land Costs

Economic forces have a major effect on land values and development density. When geographic factors limit the supply of developable land while demand remains strong, land values and density rise. Land becomes too expensive to devote large areas to surface parking and low yields. In Oklahoma City, the supply of land is relatively unlimited and land values in most areas have historically been low. As a result, there has been little economic incentive to build at higher densities or to bear the added cost of building parking structures. This will change in some areas, as amenities like the Bricktown Canal and eventually the Riverfront and MAPS 3 Park generate higher values on nearby land.

Development at the Rural Edge

Growth at the edges of the city has long presented significant challenges in addition to increasing the costs of public services. Oklahoma City has experienced very low density development close to the city but beyond the reach of existing urban infrastructure. This development is usually residential and uses wells for water and self-contained waste treatment methods like septic systems. In many cases, these areas could logically and efficiently be served by extending infrastructure in the future, but their very low density does not support the cost of installing these services. This presents the City with a number of unpalatable choices: 1) It can allow this new growth, effectively blocking future sound urban development; 2) it can prohibit this development, basically telling owners that they will have to wait for years and perhaps decades before being allowed to develop their land; or 3) it can allow premature extensions of services, making everyone pay for the maintenance of infrastructure that will not be fully used for many years.

While rural residential development near the city is a problem of timing and low density, suburban multi-family growth presents a much different issue. Available land and absence of neighbors who might oppose projects often directs apartment builders to vacant sites on the edge of urban development. These sites often lack access to commercial services, community facilities, and transportation connections that high-density residential projects need.

Zoning and Land Use Regulations

Oklahoma City regulates development with traditional ordinances that have been extensively amended, but are not up to contemporary development needs. The LUTA concept uses character, intensity, and performance as the primary measures of land development. Some of the problems caused by outmoded ordinances that need an overhaul include:

- Overuse of site-specific plan approval methods like Planned Unit Developments that can micro-manage development and prevent desirable flexibility. This occurs when basic zoning ordinances do not offer adequate and reliable standards.

- Obstacles to innovative techniques like low-impact development.

- Fragmented growth and inability to mix uses in creative and flexible ways.

- Subdivisions that lack performance criteria and standards that provide open space, street connectivity, active transportation networks, and variety of uses and densities.

Most people relate to “planning” through zoning, and planokc talks a lot about land use and regulations. So it’s a good idea to review zoning in general and Oklahoma City’s zoning in particular. Our zoning ordinance, like most, divides the city up into districts, each of which has specific requirements that govern development. Most zoning districts have two groups of regulations. One group says what land can be used for. The other group establishes how the land is developed, including items like density, setbacks from property lines, height of buildings, required open space, and minimum lot size.

Our ordinance has several categories of zoning districts: base districts, special purpose districts, and overlay zoning districts. Every parcel in land in the city falls into one of the base districts, which are in turn categorized by the dominant use they allow. We have 26 base districts including agricultural, residential, office, commercial, and industrial types. Each district has different requirements and restrictions, and are generally (but not always) arranged in order of density or intensity of use. For example, we have four industrial districts, arranged from TP (the most restrictive) to I-3 (the least restrictive).

We also have 23 special purpose and overlay districts. These districts are used in specific situations, where the base districts are too general to provide adequate regulation. Some apply to districts with unique characteristics that don’t quite appear anywhere else. For example, there are special purpose districts for the riverfront, areas with special urban design requirements, Stockyards City, Uptown, and Classen Boulevard. Others address special uses or environmental conditions like the airport or operations like sale of alcoholic beverages. “Planned Unit Development”, which is a special zoning district category that provides an alternative approach to conventional zoning, adds to the complexity.

If this all sounds confusing, it is. Part of the land use concept of planokc is to make zoning easier to understand and make it a better tool to accomplish good things for the city.

Residential Land Use Patterns

More land is devoted to residential use than to any other urban use. Therefore, residential development has a huge influence on the form and physical size of the city. In new development areas, residential development is usually the “pioneer” land use, establishing itself before retail, offices, services, and community facilities. In redevelopment areas, residential is also the typical pioneering use, although public investments like the Bricktown Canal or Core to Shore area’s MAPS 3 Park help create conditions that spark new projects. Similarly, patterns of residential development in greenfield, infill, and redevelopment settings will determine if we are able to achieve Chapter Two’s vision of an efficient, inclusive, and sustainable Oklahoma City.

To date, though, most new residential development has been built in pods that separate homes of different costs and sizes, and rarely include different types and densities of housing. These separated developments also lack internal connections to each other and to the schools, neighborhood services, and community institutions that should serve them.

Commercial Land Use Patterns

Commercial land uses are just as significant as residential uses in defining the form and image of the city. Retail settings, such as regional malls, grocery stores, neighborhood shopping centers, strips, and special districts often become centers of activity and landmarks in communities. Even more important, the health and prosperity of our commercial areas are fundamental to the City’s ability to sustain itself economically. The retail sector is a major source of employment and economic growth, and sales tax revenues are the City’s primary source of funds for routine operations and services. Therefore, commercial areas must be capable of serving and attracting customers.

Commercial uses in Oklahoma City generally follow transportation corridors, producing a pattern of linear strip development. This has several undesirable effects, including a large amount of commercial frontage on major streets, extensive areas of adjacency between commercial and residential uses, and a somewhat unplanned distribution of various types of shopping areas. This linear pattern also leads to a number of centers with high vacancy as newer facilities attract customers away from older stores. Continuous commercial use along corridors also discourages other uses such as residential, especially when vacancies increase and building maintenance declines.

But there are also positive trends in the commercial environment. The city has clusters of commercial activity within the linear pattern, which can form the core of mixed use districts. Innovative new commercial centers such as Classen Curve are emerging and both older commercial districts and special character areas are experiencing a renaissance, to the benefit of businesses and surrounding neighborhoods.

Land for Employment

An adequate, well-located and served supply of industrial land both accommodates existing businesses and gives us the ability to respond to economic development opportunities. While different industries have different needs, attractive industrial areas should have good access to transportation (including the interstate system, airport, and rail), urban infrastructure, a choice of readily developable sites, and relative freedom from nearby land uses that conflict with industrial operations. Encroachment of incompatible uses (such as residential or major retail development in business parks) makes it far more difficult to assemble sites for large-scale industries or employment centers.

Many of Oklahoma City’s industrial sites follow the same patterns as commercial areas, following transportation corridors. Consequently, industrial, commercial, and even residential uses are often adjacent to each other, limiting availability of the kinds of sites needed by new industry. Some of the more isolated and underused sites are in older industrial areas, but ownership patterns, size, and environmental contamination make these difficult to reuse.

Downtown

Downtown Oklahoma City has experienced phenomenal change during the last twenty years, advanced by the MAPS program and the private investment response to its major public projects. This period has introduced new land uses and activities downtown, including housing, entertainment, recreation, hospitality, and retailing, as well as revived strength in the traditional office and service sectors. Upcoming projects like the new convention center, MAPS 3 Park and the Core to Shore redevelopment, the modern streetcar, and the Boulevard on the old I-40 right-of-way will continue this transformation.

However, significant work remains. Despite the maturing of Bricktown as a destination, Downtown still lacks a mix of land uses that reinforce each other and produce a district that is fully walkable and teeming with activity. Major advances have been made in housing development, but there is still not sufficient supply to meet demands for a broad range of types and costs. Commercial development that supports local and regional residents, a downtown employee market, and visitors, remains a largely unrealized objective.

Environmental Conservation

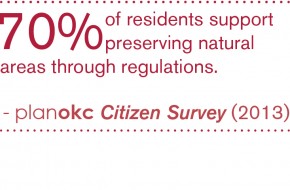

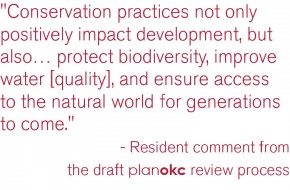

Our natural resource areas include watercourses, lakes, wetlands, and wooded areas. greenokc discusses initiatives that benefit the entire community by conserving natural resources. Currently, though, we lack land use management techniques that both protect these areas and successfully incorporate them into urban development. The priorities of land development and environmental conservation should not be seen as opposites. Rather, good conservation practices increase the value and quality of development.

Download PDF

Download PDF